What Is the Evidence Pyramid for Systematic Reviews?

What Is the Evidence Pyramid for Systematic Reviews?

A practical guide for students and first-time reviewers

When people first start a systematic review, they nearly always ask some version of this:

“What is the evidence pyramid for systematic reviews… and how do I actually use it?”

Most Google results give you the same stock triangle, a few textbook definitions, and not much else. Helpful for an exam; not very helpful when you’re staring at 3,000 records in study-screener.com or wrestling with PDFs in Excel.

So let’s fix that.

In this post, we’ll walk through:

- What the evidence pyramid actually is

- What each “level” means (in human language)

- How to use it when planning your first review

- Where the pyramid breaks down in real-world research

- Why “level of evidence” ≠ “quality of study”

- Why GRADE is becoming more popular

- How evidence tables bring the pyramid to life

- Where EvidenceTableBuilder.com fits into all this

This is written for students and first-time reviewers who want more than a diagram, but less than a methods textbook.

What Is the Evidence Pyramid?

The evidence pyramid (or “hierarchy of evidence”) is a simple visual ranking of study designs from most to least robust, based on their ability to minimise bias.

At the top, you find designs that can answer focused questions with the least confounding.

At the bottom, designs that are more descriptive, exploratory, or vulnerable to bias.

Think of it as:

“Where does this type of study start on the trust scale before we’ve even looked at its methods?”

It’s not a judgment of quality; it’s a judgment of design strength.

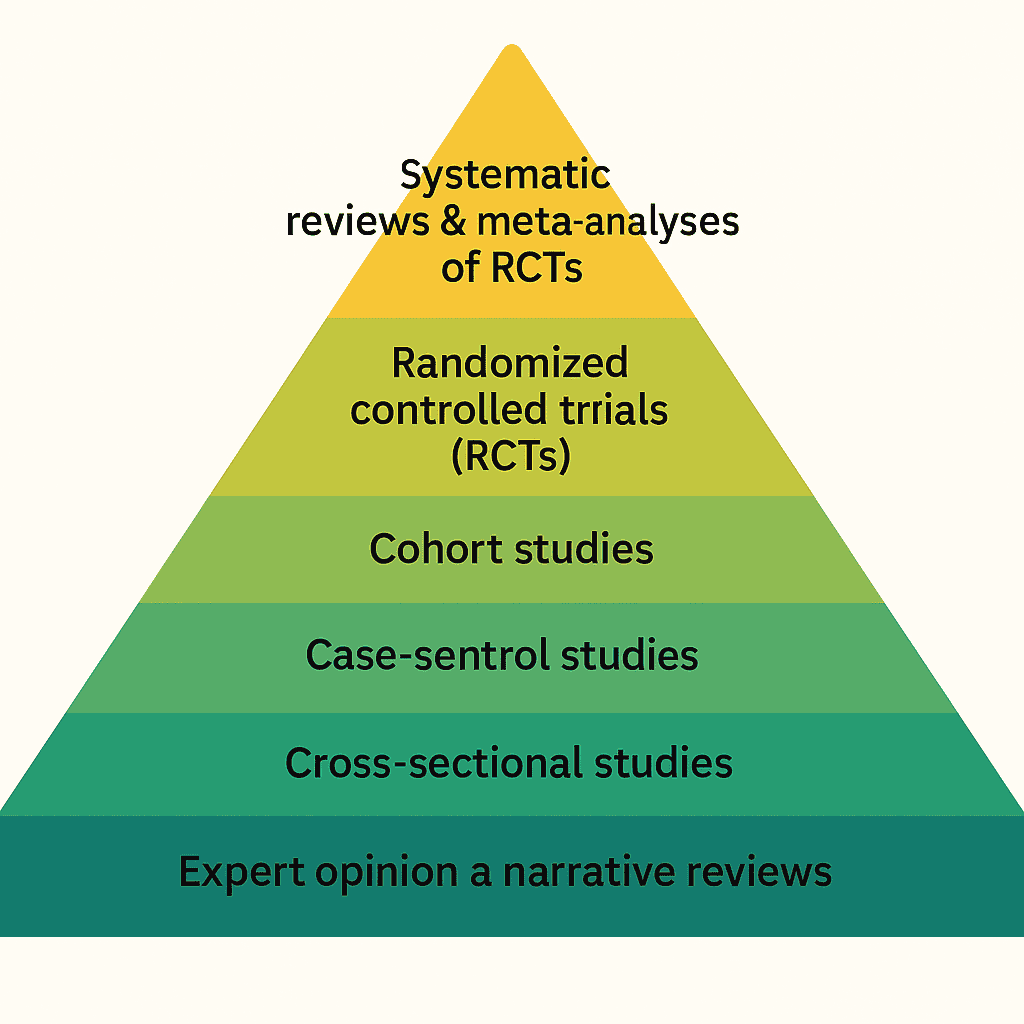

The Classic Evidence Pyramid (from top to bottom)

Different organisations tweak the details, but for intervention questions the structure usually looks like this:

Top of the pyramid: strongest study designs

-

Systematic reviews & meta-analyses of RCTs

Combine data from multiple trials → more precise effect estimates. -

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Randomisation balances confounders, making RCTs the gold standard for causal questions.

Middle layers

-

Cohort studies

Great for prognosis, long-term outcomes, and exposures. More vulnerable to confounding. -

Case-control studies

Efficient for rare outcomes but highly susceptible to recall and selection bias.

Lower layers

-

Cross-sectional studies

“Snapshot” designs. Useful for prevalence and associations; poor for causal inference. -

Case series & case reports

Early signals, rare events, clinical observations , but extremely weak for generalisable conclusions.

Bottom of the pyramid

- Expert opinion & narrative reviews

Insightful, but not systematically assembled and highly vulnerable to selective interpretation.

The pyramid gives you a structural way to think about what kind of evidence you’re dealing with , but not how good any individual study is.

How the Evidence Pyramid Helps When Planning a Systematic Review

When designing a review for the first time, the pyramid becomes a very practical planning tool.

1. It helps you anticipate what you’re likely to find

Working on a mature topic (e.g., cancer drugs)? Expect RCTs and meta-analyses.

Working on a niche topic (rare disease, new technology, specialised patient group)? You may find:

- small quasi-experimental studies

- observational cohorts

- before–after studies

- or even just case series

Knowing this early shapes expectations and prevents overpromising.

2. It guides what you decide to include

Your protocol might specify:

- “We will include only RCTs.”

- “We will include RCTs and high-quality observational studies.”

- “Due to limited evidence, all quantitative designs will be eligible.”

All of that stems from understanding the pyramid.

3. It shapes your search strategy

If your aim is RCT-level evidence, you may use trial filters or limit to controlled designs.

If you’re investigating harms or prognosis, you’ll deliberately search for observational evidence.

Different questions → different levels of the pyramid.

4. It influences your evidence tables

As you extract studies, you begin sorting them by:

- study design

- risk of bias

- outcomes

- sample size

- certainty

- effect direction

This is where the pyramid becomes a structure for how you read the field.

When the Evidence Pyramid Breaks Down (Real-World Stories)

The pyramid is neat. Real evidence rarely is.

1. When low-level designs quietly derailed conclusions

In one project, we were reviewing non-pharmacological interventions in a hospital setting. The abstracts looked convincing , lots of “positive findings”.

But once we built and sorted the evidence tables:

- The strongest effects all came from uncontrolled before–after studies.

- The controlled trials showed much smaller or inconsistent effects.

- Confounding and selective reporting were everywhere.

Without the pyramid in the background, it would have been easy to take the “positive” story at face value.

2. When solid RCTs changed everything

In another review, early observational evidence suggested a striking benefit from a specific treatment.

But when a wave of properly designed RCTs finally appeared:

- effect sizes shrank

- uncertainty narrowed

- conclusions became clearer and far more reliable

The shift up the pyramid , from observational evidence to well-designed RCTs , transformed the certainty.

These experiences taught me early in my career that the pyramid isn’t just a diagram; it’s a warning label on overconfident conclusions.

Level of Evidence ≠ Quality of Study

Here’s the part that trips most beginners:

Being high on the pyramid does NOT mean a study is high quality.

Being low on the pyramid does NOT mean a study is useless.

A poorly conducted RCT can be less trustworthy than a well-designed cohort study.

A case series can be extremely valuable for rare conditions.

A meta-analysis can be misleading if the included studies are biased.

The pyramid tells you where a study starts, not where it deserves to end up.

This brings us to GRADE.

Where GRADE Fits In (and why it’s gaining popularity)

GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) separates two things:

- Study design (RCT vs observational)

- Certainty of evidence (risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, publication bias)

Under GRADE:

- RCT evidence starts as “high certainty”

- Observational evidence starts as “low certainty”

- …but both can be downgraded or upgraded depending on their actual strengths and flaws

This is why many methodologists now view the pyramid as a useful starting point, not a final verdict.

For students, the takeaway is simple:

- Use the pyramid to understand the landscape.

- Use GRADE-like thinking to judge the trustworthiness.

How to Actually Use the Pyramid in Your First Review

A step-by-step approach

You don’t need to memorise anything. Use the pyramid as a practical workflow tool.

1. Define your target evidence level in the protocol

Make it explicit which levels you seek.

2. Tag study design during screening or extraction

Don’t wait until the end , label each study early:

- SR/meta

- RCT

- Non-randomised trial

- Cohort

- Case–control

- Cross-sectional

- Before–after

- Case series

3. Build evidence tables that respect the hierarchy

Group by design.

Highlight the most informative studies for your main outcomes.

Make the “shape” of your pyramid visible in your tables.

4. Let it guide your discussion

Your conclusion becomes more honest:

- “Most evidence came from small observational studies.”

- “Multiple well-designed RCTs consistently showed…”

- “Findings rely heavily on before–after studies; caution is needed.”

That’s what systematic reviewing is: transparent reasoning.

Where Evidence Tables (and EvidenceTableBuilder.com) Come In

The pyramid is just an idea until you build your evidence tables.

Evidence tables make the hierarchy tangible:

- every row = one study

- every column = something that matters

- a single click lets you sort by design, quality, or sample size

If you’re new to evidence tables, start with: What is an Evidence Table?. If you’re building your extraction template next, this helps with structure: What Columns Should an Evidence Table for a Systematic Review Include?. And if you’re figuring out appraisal frameworks, see: How to Choose the Right Quality Assessment Tool.

For a comprehensive guide on designing evidence tables backwards from your research question and analysis goals, see: Analysis-Driven Design of Evidence Tables.

In my own work across multiple reviews (you can find my publications by searching Burchell GL on PubMed), evidence tables have always been the moment where vague impressions become visible patterns.

It’s also why I built EvidenceTableBuilder.com , to help students and early-career researchers:

- turn messy PDF text into structured evidence

- tag study designs consistently

- compare high- and low-level evidence easily

- build review tables without drowning in spreadsheets

- actually use the evidence pyramid instead of memorising it

It’s not a replacement for your judgment , it’s a scaffold that supports it.

Bringing It All Together

The evidence pyramid is more than a diagram on a lecture slide.

It’s:

- a map of study designs

- a planning tool for your protocol

- a way to set expectations before you search

- a structure for your evidence tables

- a reminder that “level of evidence” ≠ “quality”

- a starting point for more nuanced frameworks like GRADE

If you’re starting your first systematic review and want a tool that helps you sort, structure, and make sense of your evidence base, you can try:

It’s designed to help you move from PDF chaos to clean, analysable evidence , and to actually use the pyramid in a way that improves your review.

Related reading

Tags:

About the Author

Connect on LinkedInGeorge Burchell

George Burchell is a specialist in systematic literature reviews and scientific evidence synthesis with significant expertise in integrating advanced AI technologies and automation tools into the research process. With over four years of consulting and practical experience, he has developed and led multiple projects focused on accelerating and refining the workflow for systematic reviews within medical and scientific research.