What Are the 7 Steps of a Systematic Review? A Complete Guide

If you’ve just been handed your first systematic review, it can feel a bit like being told, “Just do a really big literature review… and don’t mess it up.”

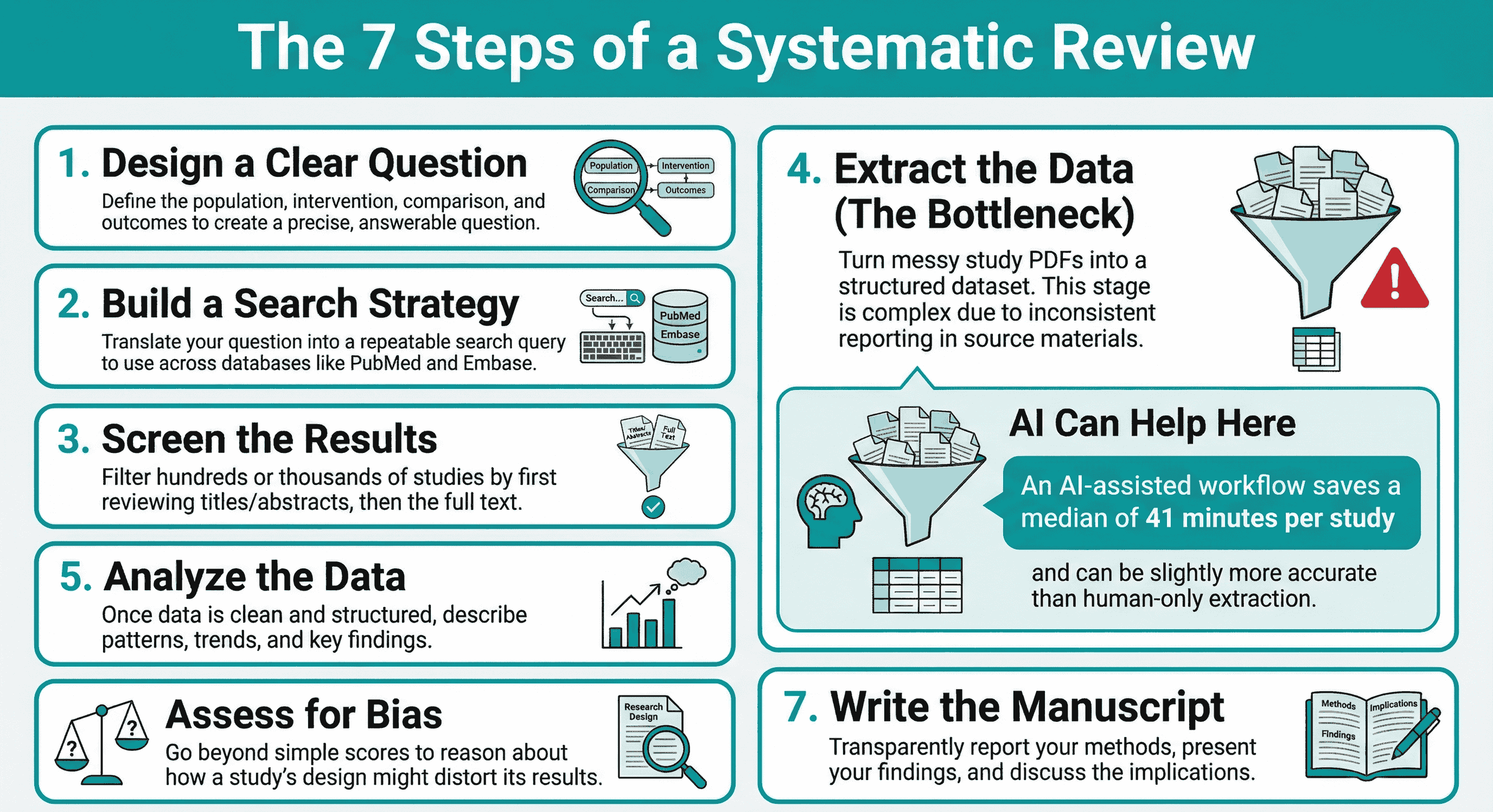

In reality, a systematic review isn’t one task; it’s a workflow made of seven linked stages:

- Research question design

- Search strategy

- Screening

- Data extraction

- Data analysis

- Quality assessment / risk of bias

- Manuscript writing

Once you see the structure, it stops feeling mysterious and starts feeling like something you can run, step by step.

This guide walks through those seven steps in plain language, with a bit more detail on data extraction and cleaning (because that’s where things often fall apart; and where AI and data extraction tools can genuinely help).

Step 1: Design a Clear Research Question

Everything downstream lives or dies based on how clear your question is.

At this stage you’re deciding:

- Who you’re interested in (population)

- What is being done (intervention or exposure)

- What you’re comparing it to (if anything)

- What outcomes you care about

- What study designs you’ll include

You don’t have to use formal acronyms like PICO, but you do need to be precise.

A vague question like “Do exercise programs help people?” becomes unmanageable. A sharper version like:

“In adults with knee osteoarthritis, what are the effects of supervised exercise programs compared with usual care on pain and function?”

…gives you something you can actually build a search, screening criteria, and extraction template around.

Step 2: Build the Search Strategy

Next you translate the question into search blocks.

For beginners, think of it like this:

- Break your question into concepts (e.g. population, intervention, condition).

- For each concept, list synonyms, related terms, and spelling variants.

- Combine them using AND/OR in databases like PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, etc.

You’re not just “Googling around”. You’re building a reusable search that someone else could repeat and get roughly the same set of studies.

Good searches feel slightly too big. You’d rather capture a few extra irrelevant studies and remove them later, than miss something important now.

Step 3: Screening (Titles/Abstracts and Full Texts)

Once the searches are done, you’ll usually have hundreds or thousands of records.

Screening happens in two passes:

- Title/abstract screening – quick decisions: obviously in, obviously out, or “maybe”. (we have a tool for this step also: study-screener.com

- Full-text screening – slower, more careful: does this study really meet your inclusion criteria?

For your first review, the main goal is consistency:

- Use the same criteria you wrote in your protocol.

- Document reasons for exclusion at full text.

- Resolve disagreements between reviewers in a structured way.

From the outside, screening looks simple. Inside, it’s a long chain of micro-decisions that sets up everything that follows.

Step 4: Data Extraction (And Why It Gets Messy Fast)

Data extraction is where you turn “a pile of PDFs” into a structured dataset.

In theory, it’s simple:

You create an extraction form and fill in things like:

- Study design

- Sample size

- Interventions and comparators

- Outcomes and timepoints

- Results (means, SDs, risk ratios, etc.)

In practice, this is the stage where chaos quietly sneaks back in.

For a detailed methodology on designing evidence tables backwards from your research question to avoid extraction chaos, see: Analysis-Driven Design of Evidence Tables.

Then, to make the extraction stage reliable (not just fast), these two posts pair well:

- Best Practices for Data Extraction in Systematic Reviews

- How Best to Use EvidenceTableBuilder for Systematic Literature Reviews

The reality of messy data

Studies don't politely line up to match your template. They:

- Report units differently (cm vs m vs “% of baseline”)

- Use different time scales (days vs weeks vs months)

- Mix scales for the same construct (three different pain scores for “pain”)

- Hide key numbers in figures, footnotes, or vague sentences

On one Sjögren’s syndrome project I worked on, the evidence base was small; but everything was inconsistent. Different outcome measures, different follow-up times, different ways of describing the same symptom. The hard part wasn’t finding the studies; it was making them comparable without breaking the logic of the review.

That’s normal. Most data extraction “problems” are really inconsistent reporting problems, not researcher problems.

Where data extraction tools and AI help

This is why data extraction tools are becoming so important for systematic reviews, especially for:

- Hospital research departments doing multiple reviews per year

- Pharma and HEOR teams running large evidence programs

- CROs and agencies managing reviews for several clients at once

- Guideline groups and HTA bodies that need transparent evidence tables “yesterday”

Modern AI-assisted data extraction can:

- Pull out structured data from full-text PDFs

- Highlight where numbers came from

- Speed up the first pass so humans can focus on checking and cleaning

Recent work in Annals of Internal Medicine compared AI-assisted data extraction with human-only extraction across six real-world systematic reviews (9,341 data elements). The AI-assisted workflow was slightly more accurate and saved a median of 41 minutes per study, when humans verified the AI output.

That’s the sweet spot: AI does the heavy lifting, humans stay in charge of judgement.

I built EvidenceTableBuilder.com for exactly this stage; to help turn messy PDFs into structured evidence tables faster, while keeping humans in the loop to verify and clean.

Step 5: Data Analysis

Once your data is extracted and cleaned, you can finally analyse it.

For beginners, this can be as simple as:

- Describing patterns in the data (ranges, trends, differences)

- Grouping similar studies

- Creating basic tables and figures that tell the story of the evidence

If you go on to do meta-analysis, great;but the key thing is this:

Good analysis depends on clean, consistent input.

If extraction was chaotic, analysis will be painful.

Step 6: Quality Assessment / Risk of Bias

Quality assessment is often misunderstood as “giving each study a score”.

That’s not the real point.

You’re asking:

- How likely is it that each study’s results are distorted by bias?

- Where could systematic over- or under-estimation be creeping in?

Tools like RoB 2, ROBINS-I, or others provide a structure, but underneath them is reasoning, not just ticking boxes. Two studies with the same numerical “score” can have very different types of problems.

Thinking clearly about risk of bias helps you:

- Interpret results more cautiously

- Explain why some evidence is more trustworthy than others

- Communicate uncertainty to decision makers

Step 7: Manuscript Writing

Only now do you get to do the bit most people think research is about: writing.

The manuscript is where you:

- Describe your methods transparently

- Present your results clearly

- Discuss what they mean (and what they don’t mean)

- Explain limitations and implications

If you kept things structured in steps 1–6, writing becomes much easier. You’re not inventing a story; you’re reporting a process and its findings.

Bringing It All Together (And Where to Start)

So, what are the seven steps of a systematic review?

- Design a clear, answerable research question

- Build a transparent search strategy

- Screen titles/abstracts and full texts consistently

- Extract and clean data (ideally with support from data extraction tools and AI)

- Analyse the data in a way that fits the question

- Assess quality and risk of bias through reasoning, not just scores

- Write up the review so others can trust and repeat your work

If you’re a PhD student doing your first review, a hospital researcher running multiple projects, or leading a pharma, HEOR, or guideline team that needs reliable evidence tables for your organisation, getting Step 4 under control is one of the biggest efficiency wins you can make.

Related reading

- Best Practices for Data Extraction in Systematic Reviews

- How Best to Use EvidenceTableBuilder for Systematic Literature Reviews

- The Most Requested Feature Is Finally Here: Audit Trails

- How to Choose the Right Quality Assessment Tool

- 5 Common Mistakes in Systematic Reviews

Want Help With the Hardest Step?

If you’d like to spend less time wrestling PDFs and more time actually thinking about your results, you can:

Tags:

About the Author

Connect on LinkedInGeorge Burchell

George Burchell is a specialist in systematic literature reviews and scientific evidence synthesis with significant expertise in integrating advanced AI technologies and automation tools into the research process. With over four years of consulting and practical experience, he has developed and led multiple projects focused on accelerating and refining the workflow for systematic reviews within medical and scientific research.